Chapter 4: Sacred Bubblegum; or, the Sal Mineo Story

It was one of those late nights at the Pickle Factory, when it was bitterly cold and yet wet out, and I wasn’t up for the long trek back to Fifth Avenue—I’d moved into Kem’s bedroom at Granny von Schlafen’s when Aunt Pudge moved away and I couldn’t live at Perry Street anymore—so I decided to crash on the floor in one of the spare sleeping bags. And then Darryle and Shelley, up making tea for themselves while working the movieola, asked me how the screenplay was coming along.

This was an old joke between them and me, about a tiny adventure I’d had last spring, a few weeks before that fateful excursion to Boston with Hornblower. Back then I told them the story about the screenplay, and it absolutely cracked them up. I’d overhear them retelling it with various improvements and embellishments, such as that David Cassidy, or rather the David Cassidy character in the script, was a sex-slave to a megalomaniac music promoter. That might well have been a subtext, although that particular aspect completely escaped me when I read it. All I got out of the script was that the teen idol was under the control of this Svengali named Bruno Sebastian, who wished to rule the world by turning all the teeny-boppers into zombies in thrall to the Bubblegum Idol.

Bruno, I figured, was going to be played by Sal Mineo, who ostensibly authored this screenplay himself. My first guess was that he didn’t really write it, because here he was asking around for someone to read it and write a synopsis. Which is how it came to me. I was told he needed a synopsis so that he could get a literary agent or producer interested. But how in hell can you write a screenplay and not know what it’s about? And not be able to write down a couple hundred words describing your story? Ergo, Sal didn’t write his own synopsis because he didn’t write the screenplay and probably hadn’t really read it either.

Later on I decided that probably Sal did write it, or some of it, and what he was really asking for is what screenwriters call a “treatment.” A treatment is a bit more full-bodied than a 200-word synopsis, though. It’s the screenplay story told in conventional narrative format, sort of like a short story. I would not have known that at the time, however. And it appears that neither did Sal.

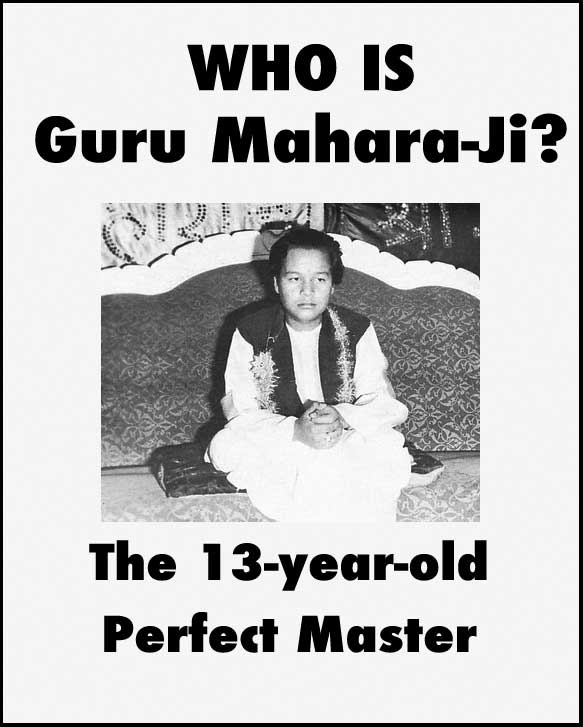

Anyway, here I was, a few months shy of fifteen, and I’m being asked to write up some kind of description of a very weird screenplay called Sacred Bubblegum. It’s called that because the David Cassidy character is not just a “bubblegum” pop singer, he’s a guru to millions of youngsters, sort of like Guru Mahara-Ji, the 13-Year-Old Perfect Master. A couple of years back you’d see posters for Mahara-Ji all around Harvard Square and Washington Square. Then he was thirteen, now he’s fifteen, so on the posters he’s the 15-Year-Old Perfect Master.

Sal Mineo was evidently much taken by all the posters that went up for this “guru.” Mahara-Ji wasn’t much to look at, but Sal thought (and I’m guessing here), “What if you had a guru who was a pop idol and looked like David Cassidy? Then even if you laughed at him, you’d still watch him, and you’d come under his spell!”

From that nugget of a concept, Sal worked up a story where this guru-idol is himself the puppet of a Blofeld mastermind type, who sits in front of his closed-circuit TV monitors and watches all the goings-on at the teen idol’s estate. From his description (about 32 years old, Mediterranean-looking), this Bruno is clearly meant to be played by Sal himself (now about 34). The David Cassidy character, whose name I forget, captures the attention of teeny-boppers not only in America, not only in the West, but all around the world. From his video cockpit Bruno watches pubescents cheer the great Bubblegum Idol in numerous languages. Presumably this is from some satellite feed, not worldwide closed-circuitry.

It galled me—no, make that amused me—to think that I was chosen for this special task because I was assumed to be part of the target audience for the screenplay, as well as being part of the age cohort doing all that raving in Minneapolis and Ibiza and Kathmandu. It’s very hard for adults to depict adolescents realistically en masse. Kids do not get crazed over bubblegum singers, any more than they would over Jerry Vale. When you see a crowd of Beatles fans screaming in Ed Sullivan’s audience back in 1964, or old newsreel clips of bobbysoxers yelling for Frank Sinatra at the Paramount twenty years earlier, those girls are not losing control, they’re playing a role. They’re doing their job, contributing to the performance.

That made for one of the funniest flubs I noticed in The Godfather movie. Instead of young, skinny, good-looking, bowtied Frank Sinatra singing at an outdoor wedding party in 1945, we get middle-aged, broad-beamed, pockmarked Al Martino pretending to be Johnny Fontane, idol of the bobbysoxers. And as he sings, the camera pans over a row of some very unattractive young women who are doing the prescribed behavior. Only they’re doing it for Al Martino, which is preposterous. Couldn’t Coppola have found a young, skinny, good-looking Johnny Fontane?

The Bubblegum Idol in the script does nothing to convince us of his overwhelming talent and charisma. Moreover he lacks plausible guru-wisdom, even of the vacuous-but-articulate sort you’d get from Alan Watts or J. Krishnamurti. We’re asked to take on faith the notion that he has psychic power; perhaps psychic power that’s being infused through him by Bruno Blofeld, sitting there in the control room. Meanwhile Bruno’s plot to rule the world through a Bubblegum Idol is never fully explained.

Since Sal chose to frame this story as a formulaic thriller rather than a farce (which would have been neat) its third-act resolution is predictable James Bond stuff. Bubblegum Boy rebels, tries to escape, and he or his fans (I truly forget) blow up the works in a huge explosion. Imagine what Sal could have done with this if he’d made it a comedy.

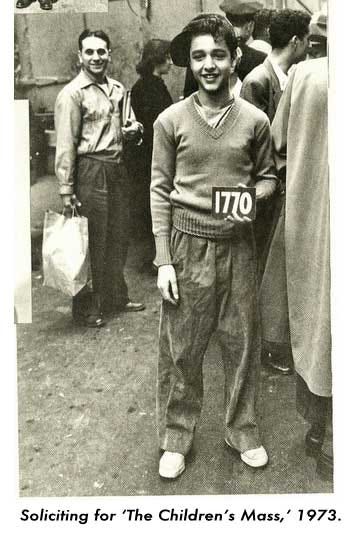

I suppose he wrote Sacred Bubblegum around 1971-72 (David Cassidy’s peak). In early 1973 Sal was in New York, co-producing a play with a friend. It was a somewhat kinky-bohemian drama called “The Children’s Mass,” more suited to the East Village’s Theatre La Mama Etc. than the respectable “Off-Broadway” Theatre de Lys on Christopher Street, where it opened and closed in the space of a week. It was written by Frederick Combs, an actor best remembered as the second lead in The Boys in the Band (movie and play). It starred, as a stunning blond transvestite junkie, their friend Courtney Burr, who wound up as a renowned acting teacher in L.A.

The stage manager for the production, Richard Flagg, lived downstairs from us on Perry Street. He seems to have volunteered my services when the play folded and Sal decided to flog his screenplay around. I guess I didn’t acquit myself very well because Sacred Bubblegum vanished without a trace, except for brief mention in a Sal Mineo biography.

Prior to this I’d always perceived Sal Mineo as a sort of mulatto. When I first saw him in Rebel Without a Cause, he was in a scene where he’s accompanied by his family’s housemaid. Well, I thought the colored maid was his mother. In the flesh and in his 30s, though, that broad touch of the tarbrush didn’t really show. He just looked like a normal Sicilian sort. I didn’t think he looked much his juvenile movie self at all, in fact he seemed almost middle-aged. Now I look at pictures of him from that time and decide I was wrong. He was still just a kid.

“The Children’s Mass” got a great sendoff when it wrapped: a slap-up dinner in Midtown for producers and company. Besides Richard and Frederick and Sal and costume/set designer Peter Harvey and the cast, they brought in Tennessee Williams, who happened to be in town because he was appearing on and off in one of his plays, “Small Craft Warnings.” I was not at the dinner (not being one of the boys in the band, so to speak) but Richard filled me in on some highlights. Apparently Tennessee was in his cups and offered an insightful postmortem about something that just might have saved the play, who knows:

“You should’ve had a dawg in the play, Fred. People lak dawgs.”